About Lichens

Lichens are a nearly perfect confirmation of Poe's concept that if you want to hide something put it in a place where everyone can see it. Many people see lichens every day of their lives but never really see them. They are found in the densest of cities, in the country, on all continents and in all habitats, even under water. Many are not in the least cryptic, growing on the sidewalks we travel (often brightly colored), on most trees (sometimes so thickly they obscure the bark), on tombstones so densely the inscriptions are often unreadable, and on rocks sometimes giving them a calico look of combinations of reds, oranges, whites, blacks, browns, greens and even bluish tints. But when one of our students conducted a survey polling Everglades National Park visitors, he found hardly anyone knew what they were. For example, he asked "What would you do if you found a lichen in your yard?". The most common answer was "Call animal control". Other responses included "Shoot it", "Stay inside" and "I don't know". Only 1 in 10 participants had any idea what lichens were.

Trentepohlia alga is in many lichens here.

For those interested, the following is a brief introduction to this amazing, insidiously secretive and understudied life form. In lay terms, a lichen results when a fungus and a photosynthetic capable partner such as an alga or a bacteria set up housekeeping together for their mutual benefit. Thus lichens are not a single life form as, for instance, a human, lion, rose or snake but a combination of at least two and sometimes three forms of life. Interestingly, a single lichen may consist of as many as three of the five Kingdoms of all life on earth, a fungus (Fungi), an alga (Protista) and a bacteria (Monera). But the important thing to remember is all lichens represent a type of synergistic relationship, often called symbiosis, (more on this later) between a fungus and one or more species of algae or bacteria (often erroneously called blue-green algae). By the term synergistic or symbiosis we mean a relationship in which each entity gives and receives some benefit. Usually, this partnership allows the entities to be more stable and better equipped to survive stresses of the natural world than when separate isolated members. Since humans have trouble understanding or caring about such relationships unless it involves them directly, let's demonstrate this concept using an average person. Even the cleanest homo sapien has hundreds of bacterial species on or within him. Some are essential to our well-being especially those found in our digestive tracts. Thus we have a very important synergistic or symbiotic relationship to the latter, i.e. they give us better health and a better chance of survival; we give them a place to live and the sustenance needed for their existence.

Now with a good understanding of symbiosis, let's look at the lichen symbiotic association which, as we have said, involves fungi, algae and/or bacteria. Fungi are not capable of producing their own food. They must attach themselves to other living or dead organisms siphoning off the nutrients of their hosts, sometimes killing them in the process. Although not all of these participate in lichen formation, some fungal examples are the whitish, stringy material under leaf litter, the discoloration under human toe nails, shelf mushrooms seen on trees (which are only the reproductive parts of the actual fungus which resides within the tree itself feeding on its host), terrestrial mushrooms, yeasts and molds. Notice that many of the foregoing reside in dark, dank, secretive niches since most fungi are destroyed or damaged by direct sunlight. They also do poorly in arid places. Thus, their distribution is quite restricted by these requirements as well as the need to be near a viable food source. Conversely, algae and the bacteria found in lichen symbiosis are able to produce their own food through the process of photosynthesis, similar to plants. However, just as with fungi, the sites where they can exist are quite restricted. Their habitat is curtailed by too little moisture and/or too little or too much sunlight. They are also favorite grazing material for many other organisms in the natural world.

We see that as separate entities, fungi and algae are not outstandingly conspicuous and, in the case of fungi, are quite cryptic. But when a certain fungus and an alga (or bacteria) join to form a lichen, an amazing transformation takes place. The outward appearance of the resultant life form usually resembles neither partner in the least. In addition, major interior physiological changes take place that allow lichens in general to survive nearly anywhere, in the harshest of environments, in any climate, in shade or direct sunlight, on every continent and on nearly any immobile substrate. The lichen association is complex and still not completely understood. In its most basic concept the fungus taps into the food source produced by the photosynthetic partner. It can therefore abandon its wandering lifestyle in search of sustenance. In return the fungus creates an environment that protects all entities while creating an optimal environment for the alga, inducing it to produce enough photosynthetic sugars for both members.

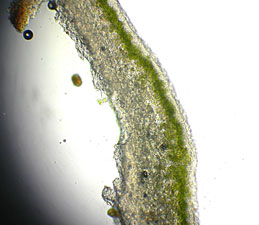

Lichen interior: alga green, fungus white.

Although this process sounds simple enough, the photosynthetic engine of the alga has to be continually fine tuned. Therefore, the fungus must ensure the alga is placed within the body of the lichen where it receives the correct amount of sunlight, neither too much nor too little. It must be protected from all detrimental circumstances. To accomplish this the fungus fabricates a variety of tools. It may develop unique fungal tissue found only in the lichen association. It may cause crystals to be produced, perhaps to diffuse harsh direct sunlight reducing the deadly effects of ultraviolet rays. It may also produce chemicals, called metabolites, which as a group provide a myriad of beneficial survival enhancing traits. In fact, as a group lichens are known to produce several hundred metabolites all of which are designed to create a protective and optimal environment in order to ensure a reliable and consistent food source. Some of the known benefits to the lichen association produced by metabolites are: (1) antibiotic properties to protect the lichen from bacterial or viral invasion. (2) chemicals which are either poisonous or distasteful protecting them from grazing predators. (3) ultraviolet light inhibitors. (4) chemicals which inhibit surrounding vascular plant growth to prevent being overgrown. (5) adjusting the membrane permeability of the algal wall to facilitate nutrient absorption by the fungus. (6) adjusting water intake or exclusion.

In a sense, in this association, fungi are farmers cultivating and nurturing a crop of algae or bacteria to ensure a food source. As such they discovered agriculture over 400 million years before humans.

Although certainly a form of symbiosis, the relationship between fungi and its photosynthetic partner(s) seems quite one sided, more resembling a master/slave association. For example, only the fungus reproduces sexually, the alga only by cell division. Thus the scientific name of the lichen becomes the same as the fungal partner involved. As alluded to earlier, the fungus may "capture" more than one photosynthetic partner, tapping the food resources of one while storing the other in special structures presumably in case of emergency.